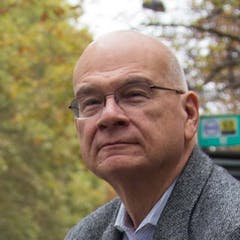

Discussion with Tim Keller (Part 1)

Good evening and welcome to Desiring God Live. My name is Scott Anderson and we’re coming to you tonight from Roosevelt Island, just across from New York City’s Upper East Side. Our guest tonight is Pastor Tim Keller. And Tim, it’s great to have you on the broadcast tonight.

Glad to have you on the island.

Very good to be here. Tim is a minister at Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City, a church which he founded in 1989. Redeemer has since grown to now having five services across three different campuses and their weekly attendance is over 5,000 people.

Before that time, Tim spent nine years in Hopewell, Virginia, pastoring a church there, and during that time he also served as the Director for Church Planning for the PCA. Tim grew up in Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania and he received his education from Bucknell University, from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, and from Westminster Theological Seminary. Besides pastoring, Tim also has authored several books including Ministries of Mercy and the New York Times bestseller The Reason For God.

He also wrote a book entitled The Prodigal God, and another entitled Counterfeit Gods. And then he’s also produced a DVD and book study series entitled The Gospel in Life.

Tonight on the broadcast we’re going to focus on Tim’s latest book, which is entitled Generous Justice: How the Grace of God Makes Us Just. Tim is married to Kathy and they have three sons, and again, thank you for having us in your home. I appreciate that.

That was amazingly accurate and a wonderful reminder to me of several things I’d almost forgotten.

Well, very good. Well, we want to kick off the broadcast tonight by just talking a little bit about you and your life, so I wonder if we could start with the home you grew up in and maybe take us through just growing up and to the point at which you became a Christian, your conversion story.

Well, I was raised in Pennsylvania, in a middle class home. Since we’re doing a spiritual narrative, I was raised in a Lutheran church, not a conservative Lutheran church. I think back then it was called the LCA (Lutheran Church in America). I went through what they call their catechetical class and learned parts of the Augsburg Confession, and it was two years and I was confirmed and baptized in the Lutheran church.

I went off to college and had probably what many kids raised in the church had, which was a lot of questions both intellectually about whether Christianity was true. I also had plenty of temptations to not lead a Christian life. But more than halfway through my freshman year, I was dragged off to an InterVarsity Christian Fellowship meeting. I really heard the gospel. It wasn’t so much that I heard the gospel in the meetings, but I actually, in a sense, discovered the gospel through reading InterVarsity Press books, or the kind of books that InterVarsity back in those days had. So they tended to be John Stott books, J.I. Packer books, and of course, some C.S. Lewis. And it was really a tonic. I saw a thoughtful kind of Christianity.

I think I became a Christian somewhere in my junior year, though maybe I can get back later on and say that actually going to seminary and understanding the gospel more fully makes both my wife and I wonder whether we may have actually gotten converted in seminary. But essentially through InterVarsity, I became an evangelical Christian and decided to go into ministry and went off to Gordon-Conwell. And actually, it was out of Gordon Conwell that I became a full-time pastor of a congregation at the age of 24 in 1975. So that’s the narrative.

Talk about that a little bit then from the college days too. When did you sense a call to pastoral ministry where you knew this is what you wanted to give your life to?

Well, I was very active in InterVarsity and I enjoyed leading the Bible studies and doing the kinds of ministries that student leaders did. I found them very, very satisfying. So I probably got involved with InterVarsity my freshman year, and had something of a spiritual crisis and made a commitment during my sophomore year. I became very active as a leader by my junior year. So by the end of the junior year, I was already pretty sure I wanted to go into ministry.

All right. Talk to me a little bit then about West Hopewell Presbyterian Church in Hopewell, Virginia.

It’s a contrast to the church I have now. Hopewell is an industrial town in the South. It does not grow or shrink much. I notice that its census figures have almost been the same through the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. It’s pretty interesting. It’s what you’d call a working class community. And I became the pastor of a church there that was hurting at the time. It needed a lot of renewal. They had some problems with the pastor before, which isn’t all that surprising, and there was division in the church. So I had what I would say is a traditional pastorate there, but I learned the ropes. The people, even though I was very young, loved my wife and I. Many of them were very simple people, so I could not put on intellectual airs. As my wife says, I learned to put the cookies on the shelf for everybody. It was down far enough that it was accessible for everybody, not way up high.

It was really a great time. And I actually feel that there’s a tendency for young ministers to think the best way to learn the ministry is to go be an assistant pastor to some great grand high poobah guru at some great church. And then get mentored and go off and do something else. The trouble is when you do that, you’re a specialist. No matter how much you might learn from how vital a big growing church is, if you’re there as an assistant, you’re a specialist. You’re not marrying and burying and counseling everybody from age 80 to age eight. You’re just not doing everything. You’re also probably not preaching as much.

Starting at age 24, I preached Sunday morning, Sunday night, and Wednesday night. I had two weeks off a year. I also did probably a wedding and a funeral every month, and I spoke at the nursing home. I remember when I got done with my nine years in West Hopewell, I had something like 1,400 expositions that I had done at the age of 33.

Wow.

I also had a loving congregation that dealt with me as a young man and was pretty compassionate and understanding. I love that particular way in which I was prepared. And I do think that people underestimate just going and taking a regular old church and just doing the job for a number of years as a young minister.

You speak of those years very affectionately.

Well, Hopewell is a working class town, so people don’t move. If you lose your job, this is where you’re from and you look around for other jobs. You don’t move. So even though we’ve been gone for 25 years, we still have lots of friends there, because they’re there. And so we show up there, even though it’s been 25 years, and we know lots of folks. We still do.

Well, let’s fast-forward a little bit then to the fall of 1989.

That’s going very fast, whisking through my life.

There was a little Bible study happening just over here on the Upper East Side. I’m curious as to the beginnings of Redeemer. What was happening in that Bible study and what became clear during that time that made you decide, “Yeah, we want to go for this, we want to start a church”?

Well, the order was a little different. I was teaching at Westminster Seminary, but I was also part-time on the staff of the Presbyterian Church in America’s Home Missions Board, which was called Mission to North America. And because of that, they were asking me to research Manhattan as a place for possible church planting. So I actually got to know some of the people up here who were interested in getting a church started. I tried at first to get other people to come. I had only been at Westminster for probably three or four years and I really liked it, and I didn’t want to go. I was looking for somebody else.

So how many people turned it down?

Well, more than one. But there were two people very definitely that we pushed and recruited, both of whom are pretty good friends of mine, still, by the way. And for various reasons, the doors weren’t opening for them. At a certain point, some of the people in that core group said, “Why don’t you try the idea out?” And Kathy and I felt that God was calling us.

Then how long was it when you started meeting with this core group before you decided, “Yeah, this is going to work and we’re going to go for this thing”?

I think probably in the fall of 1987 I started coming up here to meet with some people and found three or four couples that looked pretty interested in starting a church. Three of them eventually became part of the original core group. So I was meeting with them and trying to learn the lay of the land up here. One of the couples was the one who said, “Why don’t you consider it?” Once we decided to come, we said, “Let’s gather a group of people and start Bible study.” The moment we first met with the weekly Bible study, we already knew we were going to come. But I came up from Philadelphia once a week on Sundays, and I always took one of our three sons. We didn’t want to have all three at once because we were afraid nobody would ask us back if we had all three at once.

How old were your boys then?

Well, in 1989 they would’ve been between six and 10, that kind of thing. So we would come up and we had the Bible study probably from February of 1989 to April. Then in April we started an evening service, and the evening service was weekly from April through June. Then we moved here. We kept up the evening service until September and we went to a morning and an evening service, and that was really when we got launched. So the Bible study started after we decided we were going to come, no matter what.

Oh, I see.

We didn’t try it out, but we did know a couple of the couples over the two years when we were trying to weigh whether we should come.

Now in those early days, did you have a clear sense from the research you had done that you wanted to reach young urbanites, that you wanted to be gospel centered, that you wanted to try to affect change spiritually, socially, culturally, and that you care about cell groups and small groups? How much of the current Redeemer vision was in kernel form back then? Or were you guys just trying to gather people and make this thing fly?

No, that’s right. It was in kernel form. We were talking to people about it, about almost all those things. If I look at my oldest handouts, things that I prepared to discuss with even the earliest group, almost all those things are there in embryonic form.

I was 38 when we moved here and turned 39 just a month or two later. So I don’t know where you put that in a person’s life. I wasn’t exactly a young man anymore. I had already spent 15 to 20 years in ministries, so I had actually developed a lot of my ideas. So I wasn’t a kid, but I was still young enough I think at that point to be flexible, to learn new things, and also to appeal to a lot of young people.

Did you have other leaders that you were able to recruit into this or did you raise up from within with your core group?

Well, first of all, I had great lay leaders. I had an interesting combination of Campus Crusade for Christ folks, who Kathy and I look back on and say, “They put the evangelistic genes in Redeemer,” if you want to call it that. The evangelistic DNA of Redeemer to a great degree was inserted by them. We also had a lot of Presbyterians and Reformed folks who wanted to really make sure that the theology was there. And it was a wonderful merger of high regard for theology and a real passion for personal evangelism. That came from the lay people. And then, yes, because the church grew, we stepped out and we started bringing on some pastors and they all put their fingerprints on it as well. So it really wasn’t just Tim and Kathy’s church by any means, even from the word go.

That’s remarkable. Let me ask you a little bit about the centrality of the gospel. I’m curious as to when the realization that the gospel is for all of life became important to you personally? When did it capture your own heart? And then when did it begin to shape your pastoral ministry, both in terms of how you preach, as well as sort of your overall philosophy of ministry?

First of all, we have to be so careful when we say, “We are a gospel centered church.” Virtually any evangelical or Protestant church would say, “We’re gospel centered,” and in a certain sense they are. But what happened at Gordon-Conwell largely was that I took a set of courses with Richard Lovelace, basically on revivals. He had a course called “Dynamics of Spiritual Life”, out of which the book came. And I was in the first version of that.

He also had a course called “Evangelical Awakenings”. Essentially in there he basically proved to me that historically, even though people believe the doctrine of justification by grace through faith alone, they lose their grasp on it somehow. They lose the idea of the implication of it. They lose the joy of it. They believe it in their head, but it doesn’t actually work itself out. Very simply they still feel that at the heart level, they’re still earning their salvation. And as a result, everybody’s touchy and insecure and weighed down and burdened. If you give them a test, they’ll give you the right answers on justification by grace and faith. But revivals happen when that doctrine actually gets recovered and people say, “Oh, so wait a minute, that’s what it means.” And that all came out in those early courses.

Secondly, my wife and I took these courses together, Kathy, because I met her at seminary and we got married before we left seminary. The second set of courses that got that across were Meredith Kline’s courses on Covenant. And Kathy would actually say that even though she was very active in Christian activities and so on, it wasn’t until she was in Meredith Kline’s course that she understood this basic idea. In the covenant, there’s blessings and curses. If you obey the covenant, you’re blessed. If you disobey, you’re cursed. Jesus Christ comes to Earth as a human being, becomes a servant. Even though he’s Lord, he becomes a servant and he fulfills the covenant. He obeys the 10 Commandments. He loves God with all his heart, soul, strength, and mind, and he loves his neighbor as himself.

At the end of his life, what does he get? What should he get? He deserves the blessing. He’s the only human being who ever entered into a covenant with the Father and fulfilled it. He deserves the blessing. But instead of taking that blessing at the end of his life, he puts his head in the noose, and he takes what you and I deserve because we’re covenant breakers. He takes the curse. So he earns the blessing of the covenant, but instead takes our curse of the covenant so that when we believe in him, we get his blessing.

And it wasn’t until we were in that class and heard that, that we actually figured out what justification was. It wasn’t just a pardon. It wasn’t just that God now has pardoned us. Kathy and I basically thought what that meant was that God pardoned you and then you had one more chance and maybe another chance, and another chance, and another chance, to really live a good life. It wasn’t until we understood imputation — though Kline was using covenantal language that you get the blessing which he earned, and he gets the curse that you earned — that we really understood that. We even heard the word imputation, but the penny didn’t drop. And we realized we actually had been earning our own salvation.

Then there was a third thing in seminary. Even though Ed Clowney was at Westminster Seminary, he wasn’t at Gordon-Conwell Seminary. Ed Clowney came up and did a series of lectures on how you had to preach Christ from every text. And that if you didn’t preach Christ in the end of a text, you were basically preaching what he called a synagogue sermon, a sermon that could be preached in a synagogue, or a mosque almost, where you were just telling people how they had to live and not showing that only through Christ could you possibly live that way and that only because of Christ could God still accept you even though you don’t live that way. In other words, you have to get to Jesus.

I never quite put all the three together. Here was Kline’s covenantal theology. Here was Clowney, saying, “Preach Christ every time, otherwise you’re being moralistic.” And here was Richard Lovelace saying that you have to somehow get just the gospel out of people’s brains and into their heart, into the very center of their lives, and show them that this transforms everything. Otherwise they just keep it in a compartment and there’s deadness all through their life and the church.

I got that, I thought it was exciting, and I got out into the flat of my ministry and I really had no idea how that actually fleshed out. In the end it probably took me through most of my nine years at West Hopewell. Slowly I started to figure out how to preach the gospel better. It happened very much in increments. I went to Westminster Seminary, taught in Philadelphia there, but I went to Jack Miller’s church. At New Life, Jack showed me another level of how you use the gospel in people’s lives to bring about renewal. And I began to connect the way I saw ministry go at New Life Church with Lovelace. Actually, I learned a lot of things in seminary that I basically had the blueprints of in my head. I just didn’t know how to flesh them out.

My experience at West Hopewell and my experience in Philadelphia at New Life put me in a position where I felt like, “Hey, if I could just start a church now, start one without any tradition, I think I know how this all fits.” So when I got started at Redeemer, I had all those ideas about the centrality of the gospel in my rhetoric, in my presentation, and in my vision. I still wasn’t sure how it would fit exactly, how it would work out, especially in an urban area. So I would say it was very, very incremental. I had the foundation in seminary, spent about 15 to 20 years figuring out how it worked out, and then said, “Now give me a place to stand and I think I can do this. I really think we can bring this about.” The fact that it was in the middle of Manhattan was pretty ambitious, I suppose. But as it has turned out, God wanted us to do it that way. That’s a long answer, but I can’t help it because that was a hard question.

So your time at Redeemer has been a continued refining of that in your preaching, massaging this into every aspect of the church program and that kind of thing?

Sure. I’ve been at it for 21 and a half years, and so I can even see it. People now, unfortunately, parse my sermons, they listen to my sermons, and then they write to me about them. And I can see that even 10 years ago — I was 50 years old 10 years ago — that I was still preaching a little differently than I am now. So I feel like I’ve improved and I hope I continue to.

Sure, sure. Well, let me talk about influences. You mentioned a few in the answer to that question, and as it relates to just your own spiritual formation and the crystallizing of certain theological viewpoints and aspects of the gospel, that type of thing. I’d like to just throw out some names.

Okay.

If you can, just respond by just telling us and maybe helping our viewers that might not know who these people are. And then explain how they had a unique influence on your life. Let’s start with a theologian. Jonathan Edwards.

Do you think any of your viewers don’t know who he is?

You never know. You never know.

People who tune into the Desiring God channel don’t know who Jonathan Edwards is?

So who is he and how has he uniquely shaped your ministry?

I think where I entered Edwards is at slightly different places than Pastor John entered with Desiring God. I really entered the theology of revival. How do you renew somebody? How do you renew a church? So I read his Narrative of Surprising Conversions with tremendous interest in seminary.

Was seminary your first exposure to Edwards?

Yes. Oh, yes. I read Narrative of Surprising Conversions, Thoughts on Revival, Distinguishing Marks, Charity and its Fruits, and of course Religious Affections. I even looked at that set of sermons that brought about the initial revival, including his sermon on justification by faith. So I was particularly interested in him as a theologian of revival, though I’ve come to respect him on all sorts of fronts now.

Let me throw out another name here. Let’s go to J.R.R. Tolkien.

I don’t know what to say. Tolkien has helped my imagination. I mean, Tolkien was a devout Catholic and I’m not. However, because he brought his faith to bear into narrative, into fiction, and into literature, his Christianity — which is pretty mere Christian — and his understanding of human sin, need for grace, and need for redemption, fleshed out in fiction, has just been an inspiration to me. Whenever people ask me about this, I always do what I’m doing now. I just stutter and stammer to try to explain why it means so much.

He gives you a way of grasping glory that otherwise it would be hard for me to appreciate glory. Glory just seems to be overwhelming and even sort of abstract — glory, weightiness, beauty, excellence, brilliance, virtue. He shows it to you in some of his characters. So that’s all. I mean, when people say, “How often have you read Lord of the Rings?” the right answer is, “I actually don’t ever stop.” I’m always in it, and therefore, the number of times I’ve read it, plus his other works, is actually too many times to enumerate. I actually never stop.

So you’re always going through it.

Always.

Wow. That’s wonderful. How many years have you been doing that?

Actually, Kathy, my wife, gave them to me originally.

Wow. Well, let’s jump to another one maybe in a similar vein: C.S. Lewis.

Lewis has taught me a couple things. One is that he wrote to my wife four times when she was 12. And he actually showed me — by the way in which he always answered his letters and he would never talk down to the kids — something about the importance of pastoral care, just remembering people and thinking of people. We’ve always been very touched by that. And oh my goodness, his illustrations. Kathy and I both look back and say that immersing myself in Lewis meant I can never go more than about a minute without trying to think of an illustration. It’s not enough for me just to say, “Here’s justification.” I just need to find an illustration, because he had all these brilliant, beautiful, crystal clear illustrations. There’s a lot more than that. But I’d say he taught me as a preacher how to illustrate. As a pastor, how to care about answering your letters and getting back to people.

That’s a really helpful answer. Well, you’ve mentioned him already, what about Jack Miller? What unique role did he play in your life in forming your thinking?

Pastor Tim Keller: Jack was able to repent. He repented at the drop of a hat, but in a way that was not forced, or — I don’t know how to say it — treacly? I know that’s kind of a British word. Something sappy and syrupy. Some people are always saying they’re sorry and making you feel like, “Oh, forget I even brought it up.” But he really could repent from the heart. That was a big issue for him. He said that the spiritual giants to him were people who could repent quickly and joyfully. They didn’t do it in a self-flagellating way. It was absolutely genuine. They were very quick to admit when they’re wrong. They were not defensive at all, or making excuses. And he showed me gospel character. He really did.

Good. Let me throw out a few more names here: Dick Lucas.

Dick Lucas was the rector of St. Helen’s Church Bishopsgate. He was an Anglican minister. And he was there from the 1960s until a little after the turn of the century. He was a tremendous expositor, absolutely incredible. I actually listened to Dick Lucas’s tapes. I don’t know if you remember what tapes are. You look like a young man. But I probably listened to a 100 or 150 of his taped sermons. And probably 200 or even more of Lloyd-Jones’ sermons.

Those are two British guys who both preached to center-city Londoners. Dick was doing that more or less in the 1970s and 1980s. Lloyd-Jones was mainly doing that for the 1950s and 1960s. But my understanding of New York was that it’s more like Europe than it is the rest of the country. It’s less traditional. It’s more secular. So I said, “I am not going to learn that much by listening to really effective American preachers.”

I did want to find expositors, but I felt like the expositors who were expositing in this country were working with a much more traditional mindset. They could assume a lot more, I guess, understanding of the Bible, but even having a kind of moral furniture in their head about right and wrong. And I could see that Lloyd-Jones preached differently, especially his evening sermons, which were always evangelistic. You brought your non-Christian friends to his evening services. I listened to his evening sermons in London in the 1950s and 1960s, and Dick’s lunchtime services, which were also evangelistic. Businessmen brought their friends to them in London in the 1970s and 1980s. I thought, “Their preaching is more calibrated to the kind of person I’m going to be trying to reach.” And I think they really, really helped me a great deal. So I listened to hundreds of their messages.

Was that early in your ministry once you had started Redeemer?

Yeah. I had not listened to many of Lloyd-Jones’s sermons before that, maybe a few, and almost nothing of Dick Lucas. So in the first few years I listened to them, I said, “I’m really dealing with more of the kind of people who live in London and Paris than I am like the people who live in Atlanta or St. Louis.” And it served me well.

Okay. Well, let me throw out one more name because I think that’ll tie into our discussion here about the book Generous Justice. Tell us about Harvie Conn.

I should go back and say Dick Lucas is still alive, going strong, in his 80s. Harvie Conn has passed away, and Harvie was the chairman of the Practical Theology Department at Westminster Seminary when I was there teaching in the Practical Theology Department. So he was actually my chairman, chairman of my department. He was a missionary to Korea before he came to teach apologetics and missions at Westminster.

He was a brilliant man. I was once told by someone that he could have taught in missions or in theology or in New Testament or maybe even Old Testament. He was that good in every one of those fields. But his specialty was city urban missions. That was his love. He lived in the city and he taught urban missions and he started a journal, Urban Mission. He started several programs to train people in urban missions.

Because we had weekly department meetings and he was the chair and I was on time and nobody else was, every week I had about 15 to 20 minutes of talking to Harvie Conn. And I learned an awful lot from him, especially from the books that he was churning out. And he was one of the main reasons why I was interested in coming to New York because he gave me a passion for missions in the city. So he was very important to me, and died untimely. When I say untimely, I think he was only like 65. I was really unhappy because he was about to retire, and I expected that he would’ve turned out a good 10 or 15 years of works like Ed Clowney did after he retired. But he didn’t get a chance. So I’ve always been very disappointed with that.

Well, I appreciate you allowing that question because I think it’s fascinating to see how God has used different people in our lives, to help the penny drop in significant areas in our lives because God brought somebody across our path at some time, whether it’s somebody from two centuries ago or whether it’s somebody who’s even still alive. And to see that form is fascinating to me. You mentioned Ed Clowney earlier as well, how that different aspects of what God has called you to be as a minister have assembled themselves because of these different influences, in part because of these influences.

It is to me as well. Recently somebody else actually interviewed me on something about some of these things. It was interesting to see most of the things that you now associate with Redeemer’s ministry were actually all laid in by the time I was about 25 or 26. I just didn’t really quite know how they would flesh out. That’s except for the city piece. And the city piece came when I was in my 30s teaching at Westminster Seminary and came under the influence of Harvie, plus a couple of his colleagues, including Roger Greenway and Edna Greenway, his wife, who were on the faculty at Westminster, and Bill Crispin, who was an urban missionary with the Orthodox Presbyterian Church. So the city piece came when I was in my 30s. The other pieces were there, I just didn’t see quite how they would come together. But, oh, absolutely, none of us spring full-blown out of the forehead of God — which I know originally that story is about Zeus. He equips us through other people. That’s really important.

Well, let’s talk about that a little bit as we bring this discussion of your life story and the biographical portion to a close. You have a position of influence now with others, especially young pastors . . .

Now that I’ve made Desiring God. I mean, now this is a whole new level. I appreciate that.

Well, you, John Piper, and others, many others, for a younger generation, are the burgeoning giants upon whose shoulders a whole new generation of pastors are standing. What do you say to the young guys that maybe are watching this? They’re now early in their ministries and they’re wanting to emulate certain aspects of your philosophy of ministry, of your core message. Are there certain things that you would encourage in that regard in the same way Paul encouraged Timothy to imitate him even as he imitated Christ? And conversely, are there things that guys just ought not emulate from your life in ministry?

I’m rereading Lloyd-Jones’ book Preaching and Preachers. And he has a statement in there that I know he made elsewhere. He said, “I wouldn’t cross the road to listen to my own preaching.” And then he said, “I know nobody believes that.” I really don’t know what I want people to emulate. When I met somebody like Ed Clowney, I know that some people are looking at me like I looked at John Stott or Ed Clowney or people like that. And I know that in my head, but it’s a little bit like aging itself. Now, I know this is going to be hard for you to understand, because you’re not old. However, you know how old you are, and yet it just doesn’t sink in. I know I’m 60. Sixty year old men know they’re 60 intellectually, but we actually just don’t believe it. And that’s the reason why we do things and then we kill our backs.

We know it, and we don’t know it. We know it, and you walk on by and you suddenly see yourself in maybe a window or something like that, and you’re shocked. You say, “Oh my gosh, I really am old,” because you still think of yourself as 30. So you know it and you don’t know it. So I know that I’m seen as the way I used to look at Ed Clowney or John Stott, but it actually is totally unreal to me. So I certainly have no sense that I should be emulated. I know this. When I looked at those guys, I learned things that I said, “That is something I want to take. That’s what I want to take.” And there were a lot of other people looking at John Stott that took different things.

So I say, learn what you can. But my theory is if you cut through a tree, you see all the rings. And it’s good to kind of get really into a theology or ministry hero for a while. At one point I read all 70 existing George Whitefield sermons, because I loved him. I loved him. This was in my late 20s. But Kathy at one point, said, “So do we move on to some other hero?” She said, “In the sermon last Sunday, I thought you were on the verge of saying, ‘Methinks.’” And what you do is you go on. At a certain point, you just have to move on to somebody else. You get what you need from George Whitefield, and then you move on to some other hero.

One of the problems with modern heroes is that, because so much of what they say fits, because they’re talking to a similar audience to yours, there is a danger of getting stuck too long on a modern hero, somebody who’s a contemporary, or somebody who’s still alive. So you have to be very careful. You just have to move on. You have to not only read that person’s books. I know authors aren’t supposed to say, “Don’t only read my books.” You’re supposed to say, “Read my books.” But actually, you really have to get around. And certain things that God wants to do in you through that person will stick and other things will kind of just go past. So I really don’t know what people ought to emulate about me. What I’m trying to say is different people probably need to learn different things just like I did from the people I looked up to.

Sure. And amidst all of this people looking up to you . . .

I’m six feet four inches, so some people can’t help it.

I have short man syndrome. I look up to everybody, all five feet and eight inches of me.

That’s so humble.

Yes. Well, speaking of that, how do you stay grounded? As the books are being produced and as the sermons are being downloaded, how do you fight for humility and stay grounded amidst this?

Number one, as I already told you, it actually doesn’t feel real, just like no 60 year old really thinks he’s 60, and yet, you know you are. I mean, I know I’m getting well known, and yet at the same time, it just doesn’t feel real. It doesn’t sink in. I don’t walk around saying, “Gee, I’m really pretty well known.” It’s just like I don’t walk around and say, “Gee, I’m 60,” except some mornings.

And then the other thing is, you have to have a good marriage. I mean, I don’t know how anybody with a good marriage can get a big head. I just don’t see how that can happen. If the marriage is good, really good, your wife loves you so much that you absolutely know all of her criticism is rooted in love. And yet there’s plenty of criticism that comes from your spouse, just like back and forth. If you have a good marriage, I don’t know how that could really happen. But ultimately, I don’t know. I’m waiting for myself to start to really believe it. Kathy would say the same thing when people come and say, “Well, you know that So-and-So talked to somebody who said they’re reading Tim’s books in Timbuktu, and doesn’t that amaze you?” And she says, “No, it just doesn’t seem real.” And that’s exactly right.

So Kathy has been a gift in that regard.

Oh, yeah, and I don’t think it’s just her. I think any good spouse helps. But she’s particularly good.

She was on my list here to close out influences, actually. I know there’s a profound influence that our spouses have on us, but have there been, over the course of this journey together in God doing this thing called Redeemer, particular ways in which Kathy has been a tremendous influence or support during given seasons? Or do you view it differently now than you did back when you guys were just linking arms and jumping in together?

Well, humanly speaking, she’s the reason I’m a Calvinist, because she was Reformed before I was. I went off to seminary, not at all convinced of being Reformed. The way she would put it is she was the beginning of the avalanche. She was the first stone in the avalanche that led to it, because actually Dr. Roger Nicole, my professor there, and R.C. Sproul, who was a visiting professor there, and a lot of folks really brought me to Reformed convictions. But Kathy was the beginning. She really pushed me on that.

Secondly, she went to seminary with me. And so a lot of the things you hear me say, we’ve forged together. We would sit around and say, “Well, how would you say that?” And she’s been by far my number one sermon evaluator over the years. I know there’s a lot of great marriages. Most people notice what a big part of my thinking in my ministry she is. She’s always been sort of a part-time staff person. She’s the editor of our newsletter, etc. In the early days, she essentially did all the jobs, and she would actually say, “All 100 people on your staff are now doing things that I used to do, except for preaching.” She’s been a real ministry partner, and especially in formulating the way in which we communicate the gospel.

Amen. That’s wonderful. Well said. Well, here is just a real softball to close off this section here. A few of our viewers have asked and are curious about what a busy pastor like you, with writing and preaching and ministry opportunities and everything that’s going on, especially in this town, what do you do for hobbies? What do you do for entertainment to relax? What do you like to do?

Now, wait a minute. I’m sorry, this is not a softball question. You’re embarrassing me. Did you know that?

I did not know that. So now I’m even more eager to hear the answers.

Well, no, but Kathy says I’m really very, very weak in this area — avocations, hobbies, and things to do. New York is a hobby. This is an endlessly fascinating place. And now that I’ve done a little bit of traveling, I would put it up against any city, even some of the big great cities. I love to go to new places, new neighborhoods. It is a walking city. You just go to that place and you walk around and you see, “Oh my goodness.” You see the restaurants and the shops, and you see the religious institutions of all sorts. You see the mosques and the temples. And it’s an astounding place. So to some degree, New York is my hobby. And I have a grandchild (it’s a girl), fortunately she may really rescue me. My problem is that Kathy thinks my avocations aren’t different enough from my vocation. And therefore this has actually always been a struggle and an area where she continues to try to put pressure on me to develop them. So I’m not great at that.

Okay. That’s your holistic approach to life and ministry?

Maybe. Maybe. You can also call it working too hard. And of course, I love to read theology that I don’t have to read, frankly — theology I don’t have to read for presentation, for preaching, for teaching, or something. But that’s where Kathy says, “That’s not an avocation.” That’s what she goes after me and says, “You need to read something totally different than that. You need to go birdwatching.” And I say, “I’m not John Stott.”

Well, you’re watching Desiring God Live, and we have tonight an interview with Tim Keller, Pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church, and we’ll be back with more in just a moment.