All of Us Sinners, None of Us Freaks

Christian Convictions for the Transgender Age

Beyond gender-inclusive bathroom debates, the transgender movement has enormous momentum behind it from both major political parties in the United States, pushing toward Christians, whether we are ready or not, a number of truth-claims we must investigate.

To find the core convictions driving the transgender movement, listen to the new ways human beings are being defined and re-defined. We hear it in personal narratives like in the bestselling autobiography of Charles Mock (turned Janet Mock), titled Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love, and So Much More.

Mock’s transition story opens with a preface making it clear that words like “nature” or “natural” will not be used in the book, and especially not in reference to people who feel no disharmony between their biological sex and their chosen gender expression. Cisgender, Mock tells us, will be the substitute term for what might have previously been mislabeled as natural.

We also hear a new definition of gender coming from courtroom judges in all their regalia. Last summer, when the Supreme Court legalized gay marriage in America, Justice Anthony Kennedy announced in his majority opinion, “The limitation of marriage to opposite-sex couples may long have seemed natural and just, but its inconsistency with the central meaning of the fundamental right to marry is now manifest” (Obergefell).

With one sentence, heterosexual marriage, even if it was natural, now only “seemed natural” to a narrow-minded and bygone era now pushed aside.

For the Court’s majority and for Mock, redefining marriage and realness begins by scrubbing away any objective talk of what is natural. Here is where Christians face a problem of essential vocabulary. This is a debate over more than semantics.

In contrast, observe five basic convictions for Christians in the pro-transgender age.

1. Natural design, not tradition, offers a firm baseline for universal morals.

Contrary to Justice Kennedy, when discussing sex practices and the use of biological sex, nature is a competent guide to be heeded, not a social construct to be ignored. According to the apostle Paul, our concern is not ideological or political, it is idol-logical. This idolatry — the forsaking of God — is marked by a fumbling with natural patterns of sexuality, manifested specifically by distortions of biological sex:

Women exchanged natural relations for those that are contrary to nature; and the men likewise gave up natural relations with women and were consumed with passion for one another, men committing shameless acts with men and receiving in themselves the due penalty for their error. (Romans 1:26–27)

For Paul, gay and lesbian sexual acts are “contrary to nature” — literally “against nature.” At its heart, sex misuse is the toxic runoff of idolatry, but the manifest wrongness of the act is in leading its actors to use gender for anti-natural sex acts. Such abuse of creation is nothing short of rebellion against the Creator.

“The strength of the Judeo-Christian view of sexual expression is not in its ‘tradition,’ but in its ‘nature.’”

Natural design proves to be a firm baseline for objective Christian morality. For Paul, the strength of the Judeo-Christian view of sexual expression is not in its “tradition,” but in its “nature,” rooted in universal and irrefutable patterns of physical creation. Marriage cannot be fabricated in unions between transgendered or same-sex couples.

Even this point alone, that God has placed sexuality within the gift of marriage, seems to ask more questions than it seems to resolve. So we press in.

2. God’s pattern for gender and sexual behavior is ordered by the unstoppable pattern of procreation.

Paul’s argument against homosexual practice is instructive and ethically foundational, a cornerstone really, of all Christian thinking about the transgender revolution. But if we press in to his operating principle, Paul clearly orders all human sexuality and gender expression by the possibilities of procreation. Gay and lesbian sex acts break the natural pattern. Thus, they work against nature.

God could have designed human propagation in countless other ways, but he chose one way: two physically matured humans of complementing genders, each with unique DNA, forming a new family unity, and beget a child of the same human likeness — who will, upon conception, be given his or her own unique DNA and one of two genders, while still carrying the characteristics and likenesses of both parents.

One couple, following the pattern of millions of other couples in history, creates a family unit. Guided by a natural pattern, marriage calls men and women away from the immaturity of selfishly motivated casual sex and welcomes them into the selfless maturity of life as sexual beings living a story inside God’s natural pattern.

But this biological design for a family has global reach, responding to the call for vice regents, or image-bearers, to serve as caretakers over creation. This image-bearing calls for procreation. And this procreation calls for marriage, binary gender, and human sexuality (Genesis 1:27–28). This is the pattern of nature that must be respected in the aim of global flourishing.

“God could have designed human propagation in a million other ways, but he chose one.”

In this global design, the family unit holds together through sexuality. “A married couple does not know each other in isolated moments or one-night stands,” writes ethicist Oliver O’Donovan. “Their moments of sexual union are points of focus for a physical relationship which must properly be predicated of the whole extent of their life together.” Sexuality strengthens a monogamous bond and deepens the devotion of a couple as they welcome the gift of children. Sexuality is the means of procreation, but first it establishes a covenant unity for one couple, creating a place best suited for raising children. This is the beautiful design and purpose of the Creator. Nature calls for it.

“What marriage can do, which other relationships cannot do, is to disclose the goodness of biological nature by elevating it to its teleological fulfillment in personal relationships,” writes O’Donovan. “Other relationships, however important in themselves and however rich in intimacy and fidelity, do not disclose the meaning of biological nature in this way. They float, as it were, like oil upon water, suspended upon bodily existence rather than growing out of it.”

Biological sex, ordered to creation, roots our bodies to our deepest and closest relationships by design.

This ordering of biology helps steady the natural pattern, even in cultures where God’s design for marriage is perpetually fumbled or slanted even by the courts. Despite the rulings of human courts, biological nature holds to a pattern that will continually reset humanity. “Particular cultures may have distorted it; individuals may fall short of it. It is to their cost in either case; for it reasserts itself as God’s creative intention for human relationships on earth; and it will be with us, in one form or another, as our natural good” (O’Donovan).

3. Biological sex enmeshes us into the larger fabric of nature: past, present, and future.

A big blunder in the transgender conversation is to define one’s identity, even in contrast, with biological facts prior to a transition. Transgender stories rely on a personal right to cut off biological personhood in mid-story. Once the decision is made, the transition is started. One gender is made authentic, and the other is deemed inauthentic. Realness is redefined.

At this point, to acknowledge the nature of pre-transition biology is viewed as individually dehumanizing, a voice of anti-trans rhetoric, and borderline transphobia.

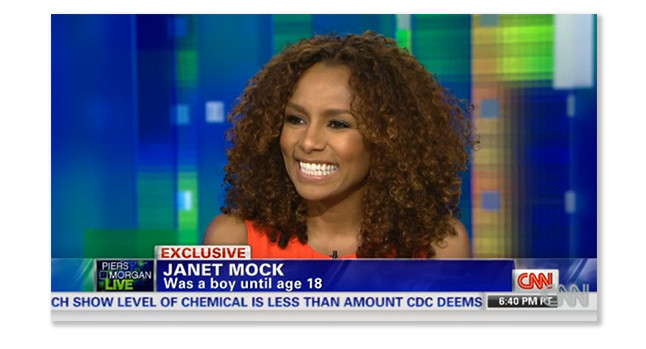

For example, when journalist Piers Morgan said Janet Mock was “formerly a man” and “was a boy until age 18,” Mock detonated on Twitter.

More basically, we should say that as Mock’s body naturally developed over the years, it emerged with a fully functioning penis and testicles, which were eventually removed surgically and re-fashioned into a sterile vagina. This statement is more awkward on a screen overlay, but it would retell an undeniable fact of Mock’s biological story — a natural fact that, if repeated, undermines Mock’s new identity and narrative.

In truth, ordered by procreation, our biological nature is intended to root our personhood into a larger embodied narrative — past, present, and future.

First, biological sex roots our present identity in nature’s past.

“Not only is the body integral to human personal identity; it is also the medium of human sociality and of human solidarity with the rest of the material creation” (Bauckham and Hart). This is a key point. The body marks our identity, connects us socially, and harmonizes us with a created pattern outside of us. Because we are fundamentally made of dust, not machined aluminum or synthetic rubber, our bodies integrate us biologically with a past history unfolding in creation history.

But our biological sex also roots our identity in nature’s future.

“Sexual gender and practice weave our lives into a much larger, organic, created pattern unfolding in history.”

If God’s design for human sexuality places us within a broader material history, then it is not only true that fabric has led to our existence, but points through us and to a future ahead and beyond us, too.

Biological sex fit us into the order of nature, writes Alastair Roberts. Our physical sex “alerts us to our bond with and belonging to a natural world beyond us, a world to which we must align ourselves, and a world for which our bodies exist.” Our bodies are oriented to the future, a future which the transgender motives often try to sever.

“Receiving the male and femaleness of our bodies and the naturalness of our male-female relation involves a recognition that our bodies are not our sole possession, but serve natural human goods, create greater realities, and are productive and expressive of a meaning beyond ourselves. In the sort of relation that exists between a man and a woman, there is a natural opening out onto realities beyond them.”

Sexual practice and gender do not terminate in us and our preferences and our autonomous identity; they weave our lives into a much larger, organic, created pattern unfolding in history.

What all this means is that a new child is not a disruptive intruder into sexual expression; the child is the very fulfillment of a purpose — the culminating moment for the gift of human sexuality, the end of a created design in nature that orders the whole realm of social relationships. Order is the key word. When marriage creates and receives a child, the pattern for human sexuality in nature shows its order, and from that order all other sexual ethics flow.

But the transgendered narrative attempts to achieve “freedom” and cuts off the biological drama somewhere mid-story. “Detached from these overarching processes and realities,” says Roberts, “sexuality and gender become properties of the abstracted individual instead, cut loose from any part in a greater drama, the author of his own autonomous narrative of self-realization, achieved through self-projection, rather than true participation.”

This is one key area where the battle over the purpose of gender is drawn. Transgender impulses de-participate men and women from a material past and a material future, and they amputate sexually active beings from true participation in the pattern. They are anti-nature.

4. Given the boundaries and aims of nature, biological sex cannot be transplanted.

Biological sex and the gender it calls forth is a physical and psychological mystery that would be almost too crazy and absurd to explain if it were not so natural and universal. Puberty, menstruation, hormones, wet dreams, orgasms, feelings of attraction, crushes, dating, waiting, marriage, sex, procreation, labor pains, and all the seasons of married life, nesting, parenting, empty-nesting, and grandparenting — these moments are gender-specific experiences that are part of one pattern, yet a pattern comprised of many elements experienced exclusively by males or females in their bodies as a part of the whole story of a shared sexual expression.

You cannot change your birth gender mid-stream in your biological story, because your gender includes how you have physically experienced the world from the beginning of life. From the chromosomal level, our particular biological sex has a long story of development in how we experience the world as engendered creatures.

“When we’re talking about someone who is transsexual, they have a very unusual relationship with their bodies,” says Roberts. “So for instance someone who is a male-to-female transsexual, they have no womb, they have no menstrual cycle, no biological clock — they don’t have the formative relationship to their bodies that women have. They are not ordered to procreation. So they are not participating in the larger pattern. In many senses, it’s a feminization of the male body and it remains a male body, and so it’s more saying this is a cul-de-sac. You cannot get anywhere this way.”

Even a uterus transplanted into a male body will never replace all the formative biological experiences of true womanhood.

In other words, according to the pattern of creation, chromosomes cannot be re-engineered, removed, or scrubbed from the software of our bodies. It may be possible for a “trans woman” to “pass” for a woman on the street at the visual level, but it is not possible for a man to morph himself into a biological woman, with all the experiences and functions of natural femaleness. The biological narrative doesn’t exist. While medical advances make it possible to suppress or change some of the outward appearances of our bodies, and change our patterns of speech and dress, it is not possible to raze our bodies to the ground and rebuild them without shortcutting all the essential formative experiences that make the biological sex expression and gender authentic.

“Fertile and functioning sex organs reshaped into disabled sexual organs is not human progress; it is the mutilation of nature.”

A “trans woman” can grow his hair long and wear high-heels and pump estrogen into his body. And a “trans man” can cut her hair short, and force testosterone into her body. All of this is an active pushing against the body’s internal software. Unable to decode ourselves from the genetics of our physical becoming, we are left to rearrange anatomical aesthetics and coerce ourselves in a direction that runs against nature.

The fact remains: “People who undergo sex-reassignment surgery do not change from men to women or vice versa” (McHugh). The developmental bond of a woman to her female body — unfolding in long stages throughout her life — cannot be replicated in a male body. A 20-year-old male body cannot become a female body with a castration leading to a reconstructed appearance of a vagina.

Fertile and functioning sex organs reshaped into disabled sexual organs is not human progress; it is the mutilation of nature. The act of surgery renders a body de-natured and now incapable of fitting into the larger created pattern for which it was made to attend. Medical technology has been asked to resurrect a body from male-to-female, and the best it can physically construct is something not far off from a man-made eunuch.

5. By resisting the transgender revolution, we reclaim the dignity of a natural pattern.

The loudest opponents of ecological pollution become mute when it comes to technological attempts to de-nature the human body. But they are not disconnected realities. “The modern domination and abuse of the natural world is not, as often claimed, the result of traditional Christian other-worldliness so much as of modern humanity’s assumption of godlike power over the world” — and specifically, godlike power over the human body (Bauckham and Hart).

If transgenderism is an attempt to alleviate the felt disharmony between body and soul — a spirit trapped in the wrong body — the redemptive hope is placed in medical technology to make it happen. This misplaced hope raises two giant cultural questions for which Christians have answers.

First: Are we creatures or machines?

It’s a relevant question with two divergent results. If we are creatures, then we have purpose and meaning in our natural being — but we also have natural limitations and boundaries. If, however, we are machines, writes Russell Moore, “we believe the Faustian myth of our own limitless power to recreate ourselves.” To protect our humanity, we must guard ourselves from the techno-possibilities that would violate our creaturehood.

Nature must always be protected from our technologies and our bodies must be protected with boundaries, because without those boundaries in place, we wield godlike technological powers over ourselves (and inside of ourselves), becoming our own creators — our own techno-re-creators.

Second: Can we escape our biological body for another?

The Christian confrontation with trans-technology is rooted in an ancient debate. As we face the transgender advocates and prophets of our age, we must understand that the disconnect between the body/soul or body/mind or material/immaterial is an ancient conversation for Christians. For millennia, Christians have been wrestling with the fully divine and fully human nature of the incarnate Christ, and in those debates the church has battled waves of ideological predecessors who have attempted to re-define the human body in their own ways.

- The church has battled Docetic ideology, which said that the physical body is merely a projection of the spirit.

- The church has battled Manichean and Flacian ideology, which said that the origin of evil is found in the material world and in the physical body.

- The church has battled Gnostic ideology, which said that the spirit is good, but the material body is an evil trap to be escaped.

Simply stated, “the idea that we are men trapped in women’s bodies or women trapped in men’s bodies collapses the distinction between sex and gender and flirts with a gnostic, even docetic, disregard for bodily reality” (Vanhoozer).

In these ancient untruths, we hear the echoes of today’s transgender advocates.

- “My body is false.”

- “My body is not the real me.”

- “My body is a plastic and moldable projection of my mind.”

The church is ready to engage these anti-nature ideologies with biblically-aware theology, but also with an attentiveness to natural design.

“Medical technology is a misplaced hope for those feeling trapped in the wrong body.”

“It is not as if God made ‘persons’ who just happen to have male or female external cladding” (Smith). No, a far deeper reality is at play. Biological sex is neither a physical prison that the spirit must escape, nor is the body simply a mirage projected by the preferences of the mind. We cannot de-participate from our biological past, and we cannot remake our material future. Our physical body, however broken and fallen, remains a gift to be received and embraced and used in continuity with the Creator’s design in nature. In this age, the church steps in to celebrate the physical structures of our lives and to resist the technology-driven hopes of the posthuman cyborgian self.

Broken, but the Pattern Holds

It is a wonderful and mysterious thing to be a creature made by Another. Yet being a creature is also frightening and dangerous. Because we cannot mute the Creator’s pattern for gender, gender becomes a battleground in the war between the Creator’s will and his creature’s rebellious desires. We have developed a culture where natural categories are relativized, and where we are endlessly told just how “trans and bi and poly-ambi-omni- we are” (Morris).

Into this culture, heterosexual marriage honors and celebrates God’s design for nature. Procreation is pro-creation, advancing human flourishing and ordering all human sexual practices, helping us delineate between what is natural and what is unnatural.

That does not mean every adult is obligated to marriage and procreation. Many will be called to lifelong singleness, like the incarnate Christ — and they are no less human for it. Some singles will struggle with same-sex attraction, and some will battle the pain of gender dysphoria. The church must become a welcoming place for brothers and sisters, willing to care for them through their very real pain, and through their potential lifelong celibacy (for those who may never find a means of sexual expression that would honor the pattern of the Creator). These are real struggles, and Christians, of all people, know that nature is broken.

Not everything works quite right (especially for those who are born intersex). Nevertheless, even in light of the brokenness of nature, when males are born with biological ambiguity, and even border on intersex, the created pattern for binary sexuality holds sure and true (Matthew 19:1–12).

For those who are not celibate, the Creator calls for the freedom of sexual expression to be bounded by heterosexual marriage. The most intimate expressions of their gender in marriage find purpose as a couple welcomes another, and with it, all the fears and uncertainties and mysteries of procreation.

Such a union, ordered to welcome another, is not threatened by ethnic diversity or by class diversity between a husband and wife. The natural pattern is not broken or threatened by adoption, nor by temporary “birth control,” and not even by the tragic reality of infertility. For those who do marry in this fallen world, who set out to follow the Creator’s pattern for heterosexual monogamy, many will discover the brokenness of nature after they marry with the full intention of welcoming biological children into the world and discover they cannot. The grief of infertility does not nullify a marriage.

Nature is broken, but the pattern holds.

Sinners, Not Freaks

G.K. Chesterton said it 88 years ago: “These are the days when the Christian is expected to praise every creed except his own.” There are many creeds we are expected to celebrate in the sexual revolution, like the one-sentence credo from French deconstructionist Jacques Derrida, now coopted by our age — “There is no nature, only the effects of nature.”

As a church, we cannot so quickly embrace the sex/gender dichotomy, nor can we cannot dismiss natural patterns, and we cannot celebrate human autonomy, but we can (and we must) love. For many, like Mock, who live with nightmares of past sexual abuse, we weep. For those who feel the pain of gender dysphoria within their bodies, we care. But into this broken world, we also speak. We offer hope. We point forward to the resurrection of the body to come.

“We cannot dismiss natural patterns, and we cannot celebrate human autonomy, but we can love.”

Until that great day when our bodies will be transformed into beings we cannot now perceive (1 John 3:2), we will stick to our own creed: there is a nature, there is an anti-nature, and we are all sinners, broken in our own ways. We are all desperately needy for grace to restore the nature of our bodies. Sexual expression is a loaded gun, handed to us for a good purpose, and it is ordered by a natural pattern. When that pattern is ignored, personal and social consequences follow.

“As Christians, all we can do is say what we believe: that all of us are sinners, and that none of us are freaks,” writes Russell Moore. “We must conclude that all of us are called to repentance, and part of what repentance means is to receive the gender with which God created us, even when that’s difficult.”